About

Purpose of This Guide

Students entering or exiting a school bus on the roadway experience risk from motorists nearby, particularly at school bus stops where students may need to cross the road. Since the earliest school buses hit the road over a century ago, the risks posed by other motorists have been increasingly addressed by the development and deployment of various technologies (e.g., stop-arms) to prevent illegal passes. Today, all states have laws requiring motorists to stop for a stopped school bus with its red lights flashing and stop signal arm deployed. Despite these advancements, school buses are still illegally passed at an alarmingly high rate. Based on a survey of bus drivers by the National Association of State Directors of Pupil Transportation Services (NASDPTS) in 2023, NASDPTS estimates that there were more than 43.5 million illegal school bus passings in the United States during the 2022-2023 school year. In recognition of the importance of identifying and combating this dangerous issue, the purpose of this guide is to present the current best practices for reducing these violations and keeping child pedestrians safe.

Local communities may be at different stages along the path of addressing this problem. To maximize its usefulness, this guide has been designed with three objectives in mind:

- Motivation – This guide is designed to motivate and encourage readers without an active program to begin to adopt strategies to reduce stop-arm violations.

- Demonstration –This guide is designed to provide tangible examples based on the successes (and failures) of previous attempts to reduce stop-arm violations for motivated readers looking for a place to start.

- Continuation –This guide is also intended to provide valuable information and up-to-date insights to refine established strategies for those who have existing programs to reduce stop-arm violations.

This guide is divided into three parts.

Illegal Passing: The Safe System Approach

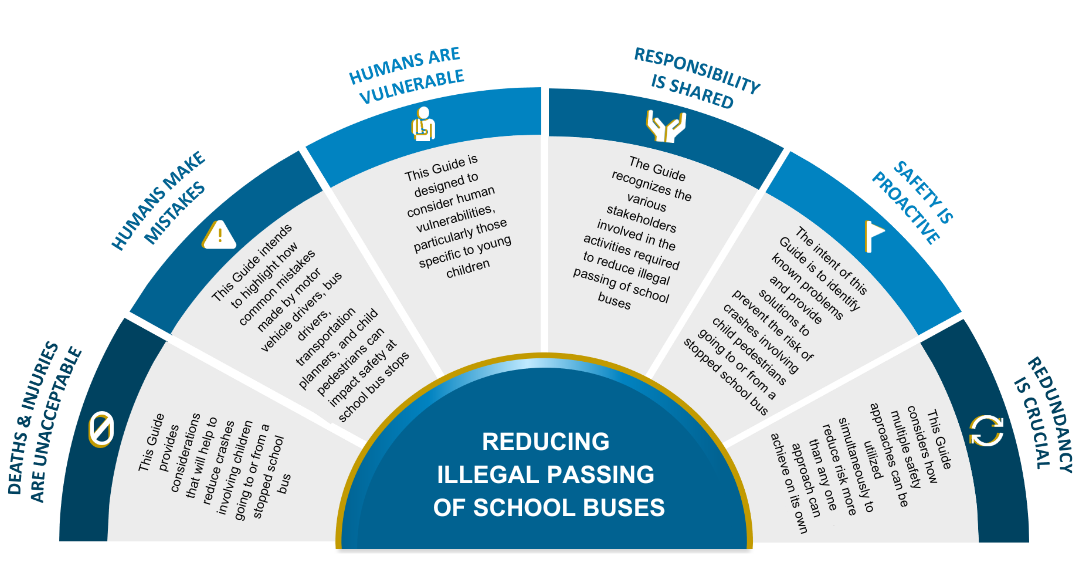

The U.S. DOT utilizes the Safe System Approach to characterize and address a variety of roadway safety issues. It is important to briefly consider how these principles can also be applied within the context of illegal school bus passing.

Illegal Passing: The Problem

Based on the annual NASDPTS survey of bus drivers, illegal passing of stopped school buses is a prevalent issue. Reducing the incidence of illegal passing of stopped school buses is easier said than done. The solution to this complex problem requires the involvement and cooperation of many groups, such as motorists, school bus drivers, law enforcement officers, prosecutors, and local judicial officials to make sure the law is obeyed, violations are reported, and the law is enforced.

Illegal Passing: Developing a Program

Every state prohibits the passing of a stopped school bus with its stop-arm out and red flashing lights on the roadway when approaching from the rear. All states also prohibit passing a stopped school bus from the front in at least certain situations (e.g., on an undivided roadway). Despite these laws, stop-arm violations by motorists continue. Several states and local areas have tried several approaches to take on this challenge. The successes (and failures) from these attempts show the elements necessary for a successful program. This guide presents lessons from these attempts in an effort to develop a "model" program to reduce stop-arm violations. This model program is described in the second part of this guide.

Safe System Approach

The following sections provide a brief overview of the Safe System Approach and suggestions for how each of the model’s core principles may factor into programs designed to reduce stop-arm violations. These suggestions are intended to demonstrate how adoption of the Safe System Approach can benefit the development or refinement of your stop-arm compliance program.

Core Principles of the Safe System Approach

The Safe System Approach is comprised of the following six key principles (for more information see Transportation.gov/NRSS/SafeSystem):

Deaths & Injuries Are Unacceptable

A Safe System Approach prioritizes the elimination of crashes that result in death and serious injuries.

Humans Make Mistakes

People will inevitably make mistakes and decisions that can lead to or contribute to crashes, but the transportation system can be designed and operated to accommodate certain types and levels of human mistakes and avoid death and serious injuries when a crash occurs.

Humans Are Vulnerable

Human bodies have physical limits for tolerating crash forces before death or serious injury occurs; therefore, it is critical to design and operate a transportation system that is human-centric and accommodates physical human vulnerabilities.

Responsibility Is Shared

All stakeholders – including government at all levels, industry, non-profit/advocacy, researchers, and the public – are vital to preventing fatalities and serious injuries on our roadways.

Safety Is Proactive

Proactive tools should be used to identify and address safety issues in the transportation system, rather than waiting for crashes to occur and reacting afterward.

Redundancy Is Crucial

Reducing risks requires that all parts of the transportation system be strengthened, so that if one part fails, the other parts still protect people.

Applying Safe System Principles to Stop-Arm Compliance Programs

The figure below includes some examples of how the core principles of the Safe System Approach can be applied when characterizing the problems – and possible solutions – surrounding school bus stop-arm violations.

The following sections provide a brief overview of the Safe System Approach and suggestions for how each of the model’s core principles may factor into programs designed to reduce stop-arm violations. These suggestions are intended to demonstrate how adoption of the Safe System Approach can benefit the development or refinement of your stop-arm compliance program.

Stop-arm compliance programs should seek to make it clear that illegal school bus passing should be unacceptable to everyone, not just a niche issue for advocates. This attitude should be reflected by bus drivers, students, parents, law enforcement, and the broader driving public. The unacceptability of these violations may also be reflected in legislation, characterizing the offenses as more serious by virtue of the penalties recommended upon conviction, and the willingness of judges or magistrates to issue sentences accordingly. As more individuals operating within the school transportation system begin to treat these violations as unacceptable, reductions in the rates of these violations should follow.

Even among well-intentioned motorists and pedestrians, there is always the chance that people will make mistakes on the roadways. Such mistakes could have serious consequences. The dangers surrounding illegal school bus passing are no exception, with a variety of mistakes that could be made by different participants in this system. Motorists may misunderstand what exceptions to school bus passing are permitted in each situation or may fail to notice a school bus while driving (e.g., if driving while distracted). Similarly, students may misunderstand safe pedestrian behavior at school bus stops—forgetting to stop and look both directions before entering or crossing the street. In short, it is unrealistic to rely on consistent, predictable, and safe behaviors of people involved in traffic at school bus stops – even among those who have been educated on proper safety precautions.

Because people make mistakes, some methods of reducing stop-arm violations may benefit from removing human involvement from the equation. School transportation administrators should ensure proper selection of bus routes and stop locations to avoid unsafe loading zones (e.g., around a sharp curve, beyond the crest of a hill, or before an upcoming turning lane where motorists may be tempted to drive on the shoulder of the road). New technologies on school buses may proactively prevent crashes, particularly those technologies that do not require any manual input from the bus driver or that are capable of automatically registering violations and collecting evidence of the offense (e.g., automated stop-arm cameras). Legislative efforts may play a role here; by crafting laws that provide as few exceptions as feasible to restrictions on school bus passing, motorists will not be required to judge such scenarios on a case-by-case basis and can consistently treat stopping as the default behavior. In short, because humans make mistakes, efforts to reduce stop-arm violations should minimize the number of decisions or actions required of the participants.

Using the Safe System Approach, NHTSA has already developed resources to assist with planning safe routes and stopping locations for school buses. For more information, see https://www.nhtsa.gov/planning-safer-school-bus-stops-and-routes.

Although all people are vulnerable to injury on the roadway, illustrating the elevated risks to students – especially younger students with less roadway experience and more fragile bodies – during school bus pickup or drop off can help to underscore the fact that illegal passing is never safe. Given the prevalence of motor vehicles in the daily lives of people in the United States, it can be easy to forget that motor vehicles weigh multiple tons and travel at speeds dangerous to pedestrians – even in lower speed limit zones. Stop-arm compliance programs should highlight the unique risks to students that exist when motorists engage in driving behaviors that may be routine in other situations. The greatest risk to a child isn’t riding a bus but approaching or leaving one. That’s why as a driver it is especially important to pay attention. Students’ lives are on the line.

Making meaningful changes in a complex, multifaceted system such as school transportation safety requires combined action from all entities involved, including motorists, students, bus drivers, parents, school administration, law enforcement, prosecutors, and the courts. Encouraging a sense of collective responsibility for safety at school bus stops can come from many sources, particularly efforts in education (e.g., info provided to parents from schools, driver education) and outreach/awareness campaigns to keep the issue front-and-center. Any of these groups attempting to take responsibility in isolation will have a limited impact on school transportation safety. However, addressing the problem together and showing how each person plays a part to help keep students safe has the potential to vastly shift the landscape of stop-arm compliance.

Unfortunately, the seriousness of illegal passing of stopped school buses is often most apparent after tragedy has already occurred. A key goal of stop-arm compliance programs should be to clearly and proactively explain the dangers associated with such violations so that these tragedies can be avoided in the first place. Technology may play a key role here: For example, developing and installing technologies that make school buses more noticeable to motorists or that alert students of an impending pass (e.g., by issuing an audible warning to stop if a vehicle is rapidly approaching). Education is another useful tool, informing motorists of both the legal requirements at school bus stops as well as the danger caused when these requirements are disregarded. Although efforts of enforcement and prosecution of stop-arm violations technically occur after a given occurrence, ensuring that the legal consequences of these violations are carried out and shared with the public can help to reduce repeat offenses and may serve to discourage would-be violators in the future. In short, preventing dangerous behavior is always preferable to reacting to dangerous behavior, so stop-arm compliance programs should seek techniques that not only punish individual offenses but also reduce subsequent violations.

Although promising methods exist to improve compliance with stop-arm laws, every technique has its own pros and cons. Because of this, programs designed to reduce illegal passing of school buses should not rely fully on any one method to improve safety. For instance, just because a school bus has an illuminated stop-arm does not mean there is no utility in having flashing red lights as well; in many cases, redundancy in the safety approaches can maximize their effectiveness. Moreover, safety techniques that are complementary to one another can be used in combination, such that the strengths of one approach are leveraged to make up for the potential shortfalls of another. For example, adding enhanced lighting technology on a school bus may improve the visibility of the bus and reduce violations, but adding in automated enforcement cameras can allow law enforcement to respond to motorists who commit violations even with this new equipment installed. As of now, no single approach has been identified as the “silver bullet” to eliminating stop-arm violations, so compliance programs should consider using a diverse array of techniques to improve safety at school bus stops.

Problem

Understanding the Problem

The big yellow school bus approaches the intersection of First and Main. Seven elementary school students are waiting near the curb to board the bus. First the yellow lights come on as the bus reduces its speed. The pace of traffic begins to shift – some drivers speed up to pass the bus before it stops, others slow down and keep their distance. Then the school bus comes to a halt and the red lights start to flash. The stop-arm goes out. The school bus driver looks at the traffic behind and in front of the bus and thinks as the children begin to board the bus, “Will any driver try to pass?” “Are the students paying attention as they board the bus?” “Can the other drivers see the students crossing the street?” “Are all the children safely seated yet?” “Will I be on time for my next stop?” The bus driver has followed every standard procedure to make sure the stopped bus is visible and signaled other roadway users to stop. Despite this, the bus driver also knows that it only takes a matter of seconds for another motorist to pass the bus, endangering the lives of students in the process.

One publication estimated 43.5 million illegal passes took place during the 2022-2023 school year (National Association of State Directors of Pupil Transportation Services [NASDPTS], 2023). The Kansas State Department of Education (KSDE) (2023) has tracked school bus loading and unloading fatalities for 53 years through their annual National School Bus Loading and Unloading Survey. The latest report provided a 53-year summary that showed 1,267 fatalities with 73% of the victims being 9 or younger (KSDE, 2023). NHTSA’s National Center for Statistics and Analysis (NCSA, 2023) reported that during the 10-year period from 2012 to 2021, there were 206 school-age children who died in school-transportation-related crashes; 42 were occupants of school transportation vehicles, 80 were occupants of other vehicles, 78 were pedestrians, 5 were pedalcyclists, and 1 was an “other/unknown” nonoccupant. These reports demonstrate the dangers of illegally passing a stopped school bus with children loading or unloading.

School buses and motorists. Both have been part of the morning and afternoon landscape for five generations of school children. Although the uniform yellow color for school buses wasn't adopted until 1939, school buses have been around since 1915 like the automobile.

In all that time there has been an uneasy coexistence between school buses and motorists. School buses make frequent stops to load and unload students. By law, in most situations, when a school bus stops and displays its red flashing lights and stop-arm to pick up or drop off students, motorists must stop too. Motorists tend to want to get where they are going, with little interruption and as quickly as possible. The existence of these competing objectives of school buses and other drivers is one of the central conflicts behind the issue of illegal school bus passing.

The act of illegally passing a stopped school bus with red lights flashing is commonly known as a "stop-arm violation." This refers to the stop-sign shaped "arm" that extends from the left side of the bus when the red lights are activated.

A recent national survey asked over 3,500 people why they think people illegally pass a stopped school bus (Wright et al., under review-a). As shown in Table 1, the top four reported reasons were that violators:

- Didn’t care (30.5%)

- Were in a hurry (25.5%)

- Didn’t know the law (24.3%)

- Were distracted (12.2%).

Table 1 . Opinion on reason for most illegal school bus passes (N = 3,557)

Opinion on Reason for Most Illegal School Bus Passes | Unweighted % | Weighted % | 95% CI* % |

They didn’t know the law | 23.1 | 24.3 | [22.4, 26.3] |

They thought the law was unnecessary | 4.2 | 3.9 | [3.1, 4.9] |

They were in a hurry | 25.6 | 25.5 | [23.5, 27.5] |

They didn’t care | 31.9 | 30.5 | [28.5, 32.6] |

They didn’t see the bus | 1.5 | 1.6 | [1.1, 2.2] |

They were distracted | 11.2 | 12.2 | [10.8, 13.7] |

They were drowsy or impaired | 0.3 | 0.4 | [0.2, 0.8] |

The bus driver made a mistake | 0.2 | 0.1 | [0.0, 0.4] |

Other | 1.9 | 1.5 | [1.0, 2.1] |

*95% Confidence Interval based on Weighted %.

These findings suggest that people may be violating the law intentionally (i.e., didn’t care, were in a hurry, thought the law was unnecessary), because of a lack of knowledge (i.e., didn’t know the law), or because they did not see the bus or its stop-arm deployed (i.e., were distracted, were drowsy or impaired). These findings suggest a multi-pronged approach is likely necessary to address the overall problem of drivers illegally passing a stopped school bus. The rest of this guide provides details on what has been tried in the past, the degree to which programs have succeeded (or not succeeded), and areas where more research and programmatic development are needed to develop best practices.

The Law

Every one of the 50 states, the District of Columbia, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands has a law making it illegal to pass a school bus with its red lights flashing and stop-arm deployed indicating it is stopped to load or unload students.

All states require the traffic approaching a stopped school bus with its stop indications to stop in most situations. While wording varies from state to state, generally the law requires the following: The school bus driver activates flashing yellow lights to indicate the school bus is preparing to stop to load or unload students. At this point, motorists should slow down and prepare to stop. The school bus driver activates flashing red lights and deploys the stop-arm to indicate the school bus has stopped and students are getting on or off. At this point, motorists should stop

State law varies in what is required on a multi-lane undivided highway or divided highway when the motorist is approaching a stopped school bus with its stop indications from the front. State law also varies on what constitutes a divided highway – for instance, whether a physical barrier is needed between each direction of travel or if a center turning lane is considered a divider. In some states, traffic approaching the bus from the front is not required to stop when on a multi-lane or divided highway. However, in all cases, traffic behind the bus must stop when the stop-arm is deployed and red lights are flashing on the stopped school bus.

Nature and Extent of Illegal School Bus Passing

While the number of actual pedestrian crashes caused by stop-arm violations is low, the potential for injury or death is high. For years, school bus drivers have been aware of, and have complained about, motorists illegally passing their school buses. Based on a survey of bus drivers in 2023, NASDPTS estimates that there were more than 43.5 million illegal school bus passings in the United States during the 2022-2023 school year. Several states, such as Florida, Illinois, New York, and Virginia, have also conducted surveys to determine the nature and extent of illegal passing more locally.

Reducing Violations

In response to NASDPTS and state surveys documenting the nature and extent of the problem, NHTSA has sponsored field demonstration/assessment programs. The intent of these programs was to try out promising approaches to address the stop-arm violation problem (i.e., illegal passing of stopped school buses) and to demonstrate what worked, what didn't work, and why. Several states and communities also engaged in efforts to reduce the incidence of stop-arm violations. The results from these efforts are incorporated as relevant throughout this guide.

Implementers of stop-arm violation programs found that increasing stop-arm compliance was not a simple task. In fact, the problem has several layers. To successfully increase stop-arm law compliance, a program must address each of the three layers and the groups involved.

This part of the problem includes three factors:

- Lack of knowledge of the law

- Lack of willingness to follow the law

- Lack of awareness of the school bus

Lack of knowledge of the law

Motorists may be unaware of the specifics of the stop-arm law and the consequences for breaking the law. A recent national survey of drivers revealed the great majority (over 90%) of people know they should stop and stay stopped in the most common situations (e.g., approaching from the front or rear on a two-lane road; approaching from the rear on a four-lane road) in which they may encounter a school bus with its stop-arm deployed and red lights flashing (Wright et al., under review-a). A demonstration project of stop-arm camera effectiveness found slightly lower knowledge of correct behaviors in those same situations at two locations with about 83% of respondents knowing they needed to stop and stay stopped (Wright et al., under review-b). While such levels of correct knowledge seem promising, the fact that about 10-20% of drivers in those two studies did not know they should stop and stay stopped for a school bus with its stop-arm and red lights flashing in these most basic/common situations is potentially problematic. The findings are indicative that more education is needed to make sure people understand their legal duties when encountering a stopped school bus and why it is so crucial they obey the law.

The national survey and demonstration project surveys mentioned above found correct knowledge was much lower regarding required motorist behaviors when approaching a stopped school bus from the front on four-lane divided or undivided roadways. This is not surprising, however, given the differences in legal requirements across states as some jurisdictions require a motorist to stop in these situations while others do not (Wright et al., under review-c). Many of the “incorrect” responses in the above surveys involved people saying they would stop and stay stopped when they are not required to do so in each state. While stopping in this situation may appear to be okay even if it is not required, it could lead to other problems such as rear-end collisions if other motorists traveling in the same direction are not expecting a sudden stop by the vehicle they are following. Developing standardized legal requirements for these situations that are the same across all states would be one way to address this problem along with school bus transportation planning exercises that prohibit having a bus stop where children are required to cross roadways with four or more lanes.

Education programs aimed at increasing public knowledge and awareness of stop-arm violation laws should be designed to achieve the following outcomes:

- Motorists need to know what the law is and, in particular, what types of highways are covered (e.g., all roads or only non-divided highways) where they live and where they drive.

- Motorists need to know what the penalty is for breaking the law. A recent national survey asked over 3,500 people to indicate the penalty for first-time offenders who illegally pass a stopped school bus in their locale (Wright et al., under review-a). Nearly three-quarters (74.1%) of participants reported they were unsure of the penalty for first time offenders. Penalties associated with stop-arm violations take many forms and differ based on

- Jurisdiction

- Witness of the violation (e.g., law enforcement, bus driver, or automated camera)

- Outcome of the incident (e.g., a monetary fine for an illegal pass itself, but jail time in the event a pupil is injured or killed during the passing event)

- Whether it is a repeated offense

For more information on school bus passing laws and penalties in the United States, see State Laws Digest on Illegal School Bus Passing (Wright et al., under review-a). NHTSA developed a social media playbook as part of its illegal school bus passing prevention campaign that provides examples of material to educate drivers about the basics of the law and what the red lights and yellow lights on a school bus mean. For more information, see www.trafficsafetymarketing.gov/safety-topics/school-bus-safety.

Lack of willingness to follow the law

Lack of information is only one reason why a motorist may not obey the law. Motorists may also intentionally disobey the law. A recent national survey asked more than 3,500 people why they think people illegally pass a stopped school bus, and the top two reasons involved drivers intentionally violating (Wright et al., under review-a).

- Didn’t care (30.5%)

- Were in a hurry (25.5%)

Although there are many different driving situations that may contribute toward decisions to intentionally commit a stop-arm violation, some other example situations include:

- Other vehicles pass a stopped school bus, so a motorist follows the general traffic pattern in a “follow-the-leader” type of situation.

- From prior experience, the motorist does not expect any children to cross the road at the bus stop, so the motorist illegally passes the bus. In this case, the motorist is unaware of the potential safety consequences.

Combined enforcement and education programs aimed at increasing traffic safety culture or increasing public knowledge of the reason behind illegal passing laws and awareness of the potential safety consequences of not following them may help prevent these types of violations.

Lack of awareness of the school bus

Drivers may have less awareness of the presence of a school bus in certain situations. In urban areas, the school bus stop may be near a traffic light. When that light turns green, motorists may focus on the traffic light and pass the stopped bus despite the red flashing lights and deployed stop-arm. On open roads where the speed limit is higher and visibility might be reduced, stopping quickly may be harder. Once they see the school bus, speeding motorists may believe they are not able to safely bring their vehicle to a stop, choosing instead to continue past the bus. Depending on a district’s morning and afternoon route times, its geographic location, and the time of year, routes may be in total darkness, making the school bus harder to notice.

Driver distraction may also limit motorists’ awareness of a school bus. The national survey discussed previously found that about 12% of drivers thought motorists illegally pass stopped school buses because they were distracted (Wright et al., under review-a).

Technologies such as enhanced lighting for school buses are on the market to increase visibility of the bus or the loading/unloading zone during a bus stop.

This part of the problem includes four factors:

- Lack of information

- Little consequence of reports

- Lack of standard procedures

- Difficulty in establishing a baseline

Before discussing each of these factors, please keep in mind that a school bus driver’s main role is to drive safely and monitor the students’ behavior. While some state laws permit a school bus driver to report violations for enforcement purposes, any methods or policies to reduce burden in this reporting should be considered to ensure bus drivers can accomplish their main role safely. NHTSA offers a School Bus Driver In-Service Curriculum that contains modules “Student Management” and “Loading and Unloading.” For more information, see School Bus Driver In-Service Curriculum.

Lack of information

School bus drivers may also be unsure of the specifics of the law in different jurisdictions, so bus drivers may need to review as part of the continuing education requirements what is and is not a violation if a state permits them to report.

Even if they do know that a violation has occurred, school bus drivers may be unsure about what exactly needs to be reported. They should review what must be included in a stop-arm violation report (e.g., license plate number, vehicle description, other specified details of the incident). Failure to record some information may unintentionally jeopardize future potential law enforcement actions.

To reduce some of the burden on school bus drivers, districts might consider the deployment of stop-arm cameras to record violations, if these cameras are permitted in the jurisdiction. This approach could allow bus drivers to focus more fully on their primary role of safely transporting and monitoring students.

Little consequence of reports

Remember that, for school bus drivers, the problem of illegal passing is not new. For many bus drivers, reporting stop-arm violations may seem to have little impact on reducing violations. School bus drivers may choose to not make a report if previous reports have not been pursued by law enforcement, or charges are ultimately dismissed, time constraints with the judicial system, and/or the incidence of the violation does not seem to decrease. Again, districts might consider the deployment of stop-arm cameras to record violations, if these cameras are permitted in the district, so bus drivers do not have additional burden from their already demanding role.

Lack of standard procedures

In many states and communities, there is no clear guidance on what a school bus driver should report and to whom the report should be made. Even when there are policies established by law enforcement for notifying motorists of probable violations or for monitoring high-incidence areas, there may not be an easy mechanism for passing information from the school bus driver to the notification agency or to the enforcement agency.

Again, districts might consider the deployment of stop-arm cameras to record violations, if these cameras are permitted in the district, so bus drivers do not have the additional burden.

This part of the problem includes three factors:

- Misgivings about the violation report

- Difficulty enforcing the law

- Difficulty getting convictions

Misgivings about the violation report

One reason for a lack of follow-through in prosecution of a reported stop-arm violation is the gray area of this violation. In many states this violation is one of the few violations (if not the only violation) that a civilian can report. Law enforcement is often uncertain about the accuracy of reports submitted by members of the public. Concerns about the accuracy and details of such reports may be alleviated by stop-arm cameras, as such technology provides objective and reviewable evidence.

Difficulty enforcing the law

Even in cases where violation reports provide complete and accurate information regarding the incident, it may still be challenging to enforcing stop-arm laws. In some states, only a law enforcement officer who witnesses the act directly can write a citation for a stop-arm violation. A violation reported by a school bus driver cannot be written up in such states, reducing the likelihood that violations will be prosecuted. It is not possible to always predict where violations will occur—even at locations with a high incidence of reports. Add to this the shortage of law enforcement officers and there is almost an impossible situation:

- To have a citation issued, a law enforcement officer must witness the violation, but

- Violations occur haphazardly, often in places that officers can't routinely patrol because they are required elsewhere.

To alleviate this issue, states may consider empowering school bus drivers not only with the authority to report events, but the training to ensure that such reports are of sufficient quality to improve the chance of successful prosecution. As stated before, stop-arm camera systems may also assist in filling this gap as they allow law enforcement to review alleged violations after the fact from a central location rather than relying on being in the right place at the right time.

Difficulty getting convictions

Even when a citation has been written, the process is not over. If a motorist chooses not to pay the fine and contests the citation, the motorist goes to court. Unfortunately, there are situations in which the charges are reduced or thrown out entirely at the judge’s discretion which reduces the effectiveness of enforcement of these risky behaviors. In certain situations, the case is dismissed for insufficient evidence. There must be evidence that a particular vehicle committed the violation. Typically this requires not just the vehicle make and color but a license plate number. In those areas where a citation can be issued based on a driver's report, bus drivers often find it hard to get a license plate number when they also have to watch the road, operate the bus, and manage the students. Indeed, it could be argued that tasking bus drivers with the responsibility of reporting such incidents could serve to distract them from the more critical task at hand: ensuring safe operation of the school bus.

Sometimes the charge is reduced because of the penalty for the violation. In some states, the penalty for a first offense is high (e.g., large fine, mandatory license suspension). Although the severity of these penalties is presumably designed to underscore the serious safety risks posed by illegal school bus passing, magistrates and judges may be reluctant to impose such penalties for a first offense.

Program

Developing a Program

When developing a stop-arm compliance program of any kind, there are three primary questions that should be asked:

- What will we do?

- Who will do it?

- How will we do it?

This section of the guide discusses how to answer each of these questions.

Most stop-arm compliance programs include four basic components:

- Enforcement

- Engineering

- Education and awareness

- Policy/legislation

A brief overview of these components is provided below. Given the variety of outreach activities that might be associated with the education and awareness component, additional discussion of such activities is included later within this section of the guide.

Enforcement

Activities in this component are designed to increase compliance with laws governing the passing of school buses. Law enforcement agencies may choose to increase enforcement of such laws at the beginning of the school year or at specific times throughout the year to reinforce the importance of these laws and to increase motorists' adherence to them.

Broadly speaking, enforcement activities can be characterized as either routine enforcement or selective enforcement. Routine enforcement means handling the violation during normal patrol duties just like other violations. In contrast, selective enforcement can take one of three primary forms:

- Concentrating on school bus passing violations if there are many stop-arm violations reported within specific bus routes or areas of departmental jurisdiction. Areas or routes with a high incidence of stop-arm violations are sometimes referred to as hot spots. Selective enforcement of such hot spots might involve officers:

- Patrolling identified intersections with high violation rates.

- Following a particular school bus.

- Riding a particular school bus.

2. Combining enforcement of stop-arm violations with other special enforcement efforts (e.g., speed enforcement, red-light running enforcement, and aggressive-driving enforcement). Often these behaviors occur together, such that attempts to identify violators for one of these offenses may not detract from detecting violators of other offenses. Moreover, selective enforcement of speed and aggressive driving may already be occurring on a regular basis for local law enforcement agencies. As such, when stop-arm compliance is added to other selective enforcement efforts, it may receive more attention than if a law enforcement agency tried to carve out time for stop-arm enforcement alone. This approach may also reduce the burden on participating law enforcement agencies by effectively leveraging preexisting enforcement efforts rather than introducing a new enforcement effort that the department may not have the resources to carry out. Further, this approach may reveal to law enforcement the need for school bus passing enforcement, potentially resulting in benefits extending beyond the targeted enforcement effort.

3. More recently, a variety of technologies have been developed to capture traffic violations including speeding, red light running, and illegal passing of school buses. These technologies aim to increase the overall level of enforcement and aim to improve compliance through deterrence. Whether stop-arm camera enforcement programs are effective in reducing illegal passing of stopped school buses has not been widely studied to date. A report on a program in Montgomery County, Maryland (Montgomery County Government, 2022) and a NHTSA demonstration project (Katz et al., 2021) provided information on the number of citations issued using camera systems. The Montgomery County program did not provide any measure of motorist behavior, so it is unclear the extent to which this program may have reduced illegal passing (Montgomery County Government, 2022). Katz et al. (2021) did measure motorist behavior with camera vendor data and bus driver reported violations. Katz et al.’s (2021) analysis of bus driver-reported violations showed decreases in violations at one of the sites after the camera policy announcement compared to before the announcement. Another site showed significant decreases in bus driver-reported violations after program implementation when comparing the pre-camera installation phase to the initial warning phases. Across all the camera vendor data analyzed in the study, only 1.87% of violators (out of 139,913 violations) were deemed to be repeat offenders (Katz et al., 2021). Another recent NHTSA demonstration project in Allentown and Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, showed that automated camera systems can identify a large number of violations (Wright et al., under review-b). According to data provided by the camera enforcement operator, a total of 5,890 citations were issued in Allentown and 2,090 in Bethlehem during the 1-year project period.

It is worth noting that enforcement efforts do not need to be completely disconnected from other components of school bus safety programs. For instance, Selective Traffic Enforcement Programs (STEPs) have been found to be an especially effective method of enforcement. These programs are implemented in waves. The first wave consists of public education and publicity to raise awareness of the law and inform the public about the upcoming period of increased enforcement. The second wave is a period of increased enforcement. This is followed by a period of normal enforcement combined with another wave of publicity to inform the public about the results of the increased enforcement. These waves (education/publicity, enforcement/publicity) can be repeated as necessary. Programs like STEPs illustrate how multiple approaches (in this case, enforcement and education/awareness) can be integrated in a way where these distinct approaches complement one another.

Engineering

This component looks at issues such as road design, construction, and signage elements intended to decrease rates of stop-arm violations or otherwise enhance safety for school bus passengers. For a stop-arm compliance program, engineering program activities might include reviewing a bus route with a high number of illegal passings to determine safer locations to load and unload students, or researching changes to the bus that would make it more visible to motorists (e.g., installation of additional exterior lights, extended stop-arms, or other engineering countermeasures). Properly implemented, addressing these elements may improve student safety without the need for involvement from program personnel.

Education and awareness

Education and awareness are major components of nearly every transportation safety program. This can encompass a range of activities, with variations dependent on the specific objective of the program and the intended audience.

Different activities are used to reach different audiences. A program to reduce the illegal passing of school buses might utilize a public awareness campaign educating parents, students, teachers, administrators, or the public to increase their knowledge of the dangers of this situation. Specific activities might include:

- Providing teachers with material they can use to help students learn the importance of looking for passing cars before they cross the street at the school bus stop.

- Sending information home to parents designed to (1) alert them to the importance of helping their children look for illegally passing cars at the school bus stop; and (2) remind the parents about their own obligations to observe the law as motorists.

- Having law enforcement officers speak to school or community groups about the dangers posed by illegal passing and what can be done to improve safety.

- Putting flyers about the law and stop-arm compliance in driver's license renewal forms sent out by the Department of Motor Vehicles.

A more extensive selection of sample activities for different stakeholders (e.g., motorists, law enforcement) is provided later in this guide.

Policy/legislation

This component includes activities aimed at getting legislation passed or policies established at the state or local level to increase student transportation safety. A program may include efforts to change legislation, or program coordinators may choose to direct efforts toward local policies. Examples of issues addressed in legislation or policies may include fines, points, and enforcement strategies. As with enforcement, policy/legislation is another component that can be effectively integrated with education and awareness efforts. Specifically, to the extent that enacting changes in policy or legislation regarding stop-arm violations requires persuading members of these executive or legislative bodies, people in these positions may benefit from outreach efforts to illustrate the seriousness of the issue and how they can use their position in society to reduce harm to students.

Specific Examples of Education and Awareness Activities

There are a variety of individuals who might be identified as ideal candidates for outreach efforts. Similarly, messaging media can take on many forms depending on the objectives of the campaign. The following section details several potential targets of education and awareness efforts as well as examples of specific activities that might be used in messaging campaigns for these various groups.

Properly timing your outreach

Sustained media programs can be costly in terms of both creating the material (e.g., video or audio messages, billboards, print ads) and placement of such messages on television, radio, social media, or other methods. If there is limited time to devote to this issue, efforts can be focused on a specific day or week of the year. This could be during National School Bus Safety Week or another designated day or week (e.g., right before school opens) to optimize the visibility of the campaign messaging in the program area. Use media (e.g., websites, social media, print, radio, television) to publicize concerns about school bus safety and the illegal passing of stopped school buses.

If your state has a way for citizens to report stop-arm violations, use the media to publicize what to do in the event a violation is spotted.

Specific messaging activities might include:

- A press conference/event that generates news articles and stories.

- Public service announcements on both radio and television.

- Televised interviews of school administrators or other public officials discussing both the scope and severity of the stop-arm violation problem.

- Advertising in newspapers, billboards, and websites.

- Social media posts by accounts associated with the community more generally (i.e., not restricted to groups specifically devoted to school bus issues as this may limit visibility for the wider public).

- NHTSA created an illegal passing social media playbook that contains sample social media content in English and Spanish. The content is designed for easy posting and seamless integration into your current social media strategy. Find the resources here: https://www.trafficsafetymarketing.gov/safety-topics/school-bus-safety

- A member of the media riding along in a patrol car behind a school bus or on a school bus to film a violation. (Remember a violation might not occur.)

Publicity about successful prosecution can also work to deter motorists, especially if the penalty in your state is severe (e.g., high fine or revocation/suspension of license).

The most effective messaging efforts are those that convince people to take personal action to address the problem and spread the message. In this way, the impact of the message reaches beyond the initial audience. Of course, motivating the public to spread awareness of the importance of this issue can be difficult. However, if crafted appropriately, successful campaigns can lead to a broader intolerance of illegal school bus passing, thereby reducing violation rates in the target community.

Even if a program only has the resources to conduct a campaign once a year, use ongoing activities to keep the safety message alive. Hearing a message once a year is not enough to make a lasting impression, so develop activities that are capable of being replicated or repeated. Social media is a cost-effective way to do this.

Outreach to motorists

In addition to messages aimed at the public, outreach devoted specifically to motorists is an important method of reducing stop-arm violation rates. Information targeted at motorists might include:

- Raising motorists' awareness about the law’s purpose: to help keep children safe. Sometimes people forget that school is in session, especially if they don't have school-age children.

- Educating motorists about the law (e.g., how and when they need to stop when encountering a stopped school bus, including scenarios in which passing is either prohibited or permitted).

- Educating motorists about the penalties they may face if they disobey the law.

- Ensuring that information included within driver license manuals is correct and up-to-date based on state laws.

Some objectives for designing a media campaign are:

- Inform the public about school bus safety laws requiring motorists to stop while a bus is stopped to load or unload children.

- Deliver the enforcement message to the entire population of the program area, clearly showing the consequences for stop-arm violations (i.e., ticket, fine amount).

- Make the public aware that a stop-arm violation will result in a ticket as cameras were installed on all school buses in the local fleets.

Below are examples of some campaign messaging tactics.

- Over-the-top: Connected TV and network

- Pre-roll video (i.e., video content that automatically plays before a featured video on desktops, tablets, or mobile devices)

- Social media video

- Digital out of home (i.e., content that is viewed outside the home including but not limited to billboards, gas station pumps, public transit, and doctors’ offices)

- YouTube videos

- Audio (digital audio sources including but not limited to Spotify, iHeartRadio Web, and Amazon Music Free).

Outreach to professionals

Beyond messaging to the public and motorists more specifically, outreach efforts may also include attempts to increase education and awareness of illegal passing among professionals associated with the detection, enforcement, and prosecution of stop-arm violations. The following sections detail activities that might be considered.

Inform school bus drivers

- Review correct stopping procedures (e.g., when to deploy amber warning lights and red stopping lights) and what constitutes a legal stop for motorists encountering a stopped school bus.

- Review what constitutes an actual violation within the state of interest.

- Review what to include in the stop-arm violation report (e.g., vehicle color, vehicle make, license plate number, or other details as stipulated by law).

- Review the procedure for making the stop-arm violation report and what happens with the report once it is filed.

NHTSA offers a free School Bus Driver In-Service Curriculum.

Inform law enforcement officers

- Remind them about the seriousness of the violation. Although the number of crashes is low, the potential for a community tragedy (and outrage) is high.

- Review the law.

- Review the state's reporting requirements and procedures. Inform prosecutors.

It is very important to know on whose word a citation can be issued. The law varies from state to state. In some instances, only law enforcement officers who witness the violation can issue a citation. In other states, a citation can be issued based on the report of a motor vehicle inspector, a school bus driver, or even an ordinary citizen. Further still, some states permit automated enforcement cameras so long as the recorded footage is reviewed by a law enforcement officer before citations are issued. In short, the role that officers play in the enforcement of stop-arm violation laws is largely dependent on the state or locality involved, so messaging efforts should be tailored in such a way that they are directly relevant and actionable for the recipients of the outreach campaign.

Inform prosecutors

- Remind them about the seriousness of the violation.

- Remind them about the importance of their part in the process. Successful enforcement and a reduction in violations depend on their prosecution of violators.

- Review the law.

- Review the state's reporting requirements and procedures.

Inform judicial officials, particularly those who hear these cases

- Remind them about the seriousness of the violation.

- Remind them about the importance of their part in the process: successful enforcement and a reduction in violations depend on their conviction of violators.

- Review the law and its associated penalties. Note how the penalties may vary based upon conditional factors such as whether the motorist is a repeat offender, whether the violation was observed by a law enforcement officer or automated camera, and whether the incident resulted in physical harm to a student.

- Remind them that it can be very difficult to track convictions (for baseline data or for repeat offenders) when the charge is reduced. In other words, while dropping charges or dismissing a case may seem prudent in some instances, understand that this action may make it difficult to prevent repeat violations and could create the appearance that the problem is less common than it actually is.

Take advantage of opportunities to meet with professionals in situations where they are already congregated (e.g., school bus driver in-service training, law enforcement roll call). Keep your information simple and brief. Use credible presenters who are known by the audience to enhance the persuasiveness of the message.

Finally, one important yet often nonverbalized aspect of outreach to professionals is remembering that professionals who deal with the issue (school bus drivers, law enforcement, etc.) need to foster their relationships in working together toward the common goal: to reduce illegal school bus passing. School bus drivers and other school transportation officials may have felt ignored in the past when they reported stop-arm violations. Any working relationship between these professionals, such as officers riding school buses, helps to foster better relationships and respect.

Possible Partners

One reality that must be acknowledged from the very beginning is that everyone who will be involved in your effort is already busy. The logical organizations to take on a stop-arm compliance program might be school transportation and law enforcement.

When brainstorming about possible partners, it is important to be creative and think outside the box to identify any groups that might be interested in helping. Consider asking yourself the following questions determine possible options:

Who already cares about this issue?

Who should care about this issue?

Who has expertise, material, or access to services that would be useful?

Your first step should be looking for community organizations that already address, road safety, injury prevention, public health and safety, or children's issues. For example, you should consider whether your community has a Safe Routes to School program or a Safe Kids Coalition (see the resources listed at the end of this guide for ways to locate organizations like these). Such coalitions may have already collected critical data and have established contacts with other community groups and local businesses. An affiliation with these coalitions can bring your program credibility and ongoing support in addition to saving valuable time by learning from their experience on what has or has not worked in their efforts to address illegal passing.

Here is a list of partners that some programs have included. Some of your partners may be involved early in choosing a structure and possible activities, while other partners may join as the activities are developed. Finally, a clear understanding of the current or expected limitations of your organization when implementing a program is key to identifying ideal partners with capabilities and resources that complement your own.

At the State level:

- Governor's office

- State Highway Safety Office (manages state's highway safety program; serves as liaison between governor and highway safety community)

- Department of Transportation

- Department of Motor Vehicles

- Department of Public Health

- Department of Public Safety

- Department of Education / Department of Public Instruction

- Pupil transportation associations

- School bus associations

- State police

- Chiefs of Police association

- Association of school business officials/administrators

- Association of local judges/magistrates

- Manufacturers of school bus technologies (e.g., developers of automated camera enforcement systems, enhanced school bus lighting systems, or even school buses themselves)

- Other relevant private sector entities (e.g., insurance industry, suppliers)

At the local level:

- Pupil transportation services in school districts

- Law enforcement agencies

- Emergency medical services or post-crash care

- Media

- Prosecutors

- Judges, magistrates

- Community public health groups

- Parent/teacher organizations

- Youth

- School board/administrators

- Community and service organizations

- Safe Kids Coalitions

- Safe Routes to School programs

- National Safety Council chapters

- Local hospitals/trauma centers

- Local branches of civic clubs or service organizations (e.g., Kiwanis, Rotary International, Lions Clubs)

- Traffic safety alliance/association

- Community health workers

- Injury prevention associations and liaisons

- Local research universities

- Neighborhood watch

- Faith-based organizations

- Local private sector entities (e.g., local businesses, hospitals, utility companies)

Organization and Administration

Knowing what you want to do and who you want to do it is not enough. There must be a structure for organizing and administering your program, no matter how limited or extensive your plans.

Find your partners

Use the list provided to stimulate ideas about possible partners in your area. Be sure to consider variety of potential partners in order to achieve your specific objectives. Not all partners need to carry the same weight when contributing to the project, but having a more extensive base of support gives you a larger network to reach with your message and a greater number of people to share the load. Reach out to potential partners at conferences, by email, and through press/media conferences.

The primary partners in a stop-arm compliance effort are schools, parents/caregivers, school transportation services, local public health offices, law enforcement, non-profits dedicated to child road safety, such as Safe Kids coalitions or Safe Routes to School programs, and the media. Early buy-in from these primary partners will generally improve the odds of your program succeeding.

Remember that many potential partners (even primary ones) may be unaware of the extent of the illegal school bus passing problem and they may need information—either from you, from law enforcement, or from other members of the criminal justice system—to raise their awareness. Other potential partners may be aware of the extent of the problem but need information about what they can do to address the problem.

Finally, it’s worth noting that not every program needs to be large-scale or fully comprehensive. Sometimes smaller efforts targeted at improving a single element in the overall system can reveal the feasibility of larger programs in the future. For smaller efforts such as these, do not assume that a lack of strong partnerships will cause your program to fail. On the contrary, every effort that chips away at the problem of illegal passing enhances the overall safety of child pedestrians and school bus riders.

Keep your program realistic with minimal time requirements and clearly defined criteria for success

Tell your partners what you need from them and how their efforts contribute to the program’s goals. Keep requests of partners at a reasonable level. Remember that many partners, especially those in the public sector, will not be able to contribute money. However, they may be able to help you with:

- In-kind contributions (e.g., printing your material, publicity about your program or your message, a location, or refreshments for an event).

- Time and expertise of members within the partner organization.

- Access to their professional networks or physical facilities.

- Making specific requests of individual partners.

Clearly defining and conveying the role each partner plays in the program helps everybody know where they stand. For example, you may ask the pupil transportation and school bus contractors associations to distribute your material to each of their members, or ask a local insurance company to print refrigerator magnets that you can hand out at the state fair.

Evaluate your efforts

In addition to achieving the program’s goal (i.e., reducing stop-arm violations), valuable insights can also arise from considering how the program operated, including successes and challenges. Capturing these insights can assist in further refining the current program or helping to develop other programs in the future. To this end, the sponsoring agency or primary partners should periodically evaluate the program. There are two kinds of evaluations that will help you: process evaluations and outcome evaluations.

Process evaluations

This method compares the program’s goals and planned activities with what you did. Ask these questions:

- Was the program implemented as planned?

- What audiences did you reach?

- What resources were spent?

- What problems were encountered and how were they handled?

- What lessons were learned?

- Are there new ideas that could be tried?

Use this information to get an overall picture of what you accomplished and to modify your program and future activities.

Outcome evaluations

This form of evaluation measures the extent to which the program has met its goals and created changes in knowledge, attitudes, and behavior. This evaluation assesses the program's actual impact as compared with its intended impact. Has there been a reduction in the number of illegal passes? Has there been a change in the community’s knowledge and attitudes toward the school bus stop laws or enforcement approaches?

Outcome evaluations are often much more complex and costly than process evaluations. You may need outside expertise to conduct an outcome evaluation. Check with your State Highway Safety Office for evaluators in your area. Local colleges and universities, academic research institutes, and public health agencies are also good sources of evaluation expertise. Use evaluation results to:

- Improve your program

- Publicize your success

- Get additional resources

- Gain community support

- Give credit to your partners

Resources

While this best practices guide can serve as a helpful touchstone for developing stop-arm compliance programs, there are other resources that can also assist you in this process. The following section provides a list of resources that may be useful to learn more about developing school bus passing programs or to find potential partners.

Government Entities

National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) – National or Regional Offices

The mission of NHTSA is to save lives, prevent injuries and reduce economic costs due to road traffic crashes. NHTSA pursues this goal through education, research, safety standards, and enforcement activities. NHTSA offers information, material, and technical assistance on issues related to pupil transportation, bicycles, pedestrians, motorcycles, motor vehicles, impaired driving, and occupant protection. In addition to its national efforts, NHTSA’s 10 Regional Offices work with states and other public and private sector customers to help carry out the agency’s mission at the state level. In addition, the offices promote legislation, coalition building and training and provide grant program support.

Governors' Highway Safety Representatives

The governors' highway safety representatives manage each state's highway safety office programming and serve as liaisons between their governors and the highway safety community. Their mission is to provide leadership in the development of national policy to ensure effective highway safety programs. Your state's representative is an excellent resource on many highway safety issues including occupant protection, impaired driving, speed enforcement, school bus, pedestrian, and bicycle safety.

National Organizations

National Association for Pupil Transportation (NAPT)

NAPT is an organization of pupil transportation professionals dedicated to promoting safety and enhancing efficiency in pupil transportation. Individuals in the transportation industry can find information about pupil transportation at this website. This is also a good resource to contact if you have school bus-related questions.

The Governors Highway Safety Association (GHSA)

GHSA is an organization representing the highway safety offices in the United States and its territories. GHSA's website is an excellent source of information providing countless links to highway safety-related online resources. The site also lists all State Highway Safety Offices as well as associate members of GHSA from various sectors (e.g., the automotive industry, insurance companies, law firms, research institutes, consulting firms).

National Association of State Directors of Pupil Transportation Services (NASDPTS)

NASDPTS provides leadership, assistance, and motivation to the nation's school transportation industry to provide high-quality, safe, and efficient transportation for pupils. The association works with organizations at the federal, state, and national levels that have an interest in pupil transportation.

State Directors of Pupil Transportation

The State Director of Pupil Transportation is responsible for state policies concerning pupil transportation and will be able to provide information about the state's pupil transportation program.

National School Transportation Association (NSTA)

NSTA is a national organization that serves as the trade organization for school bus contractors, companies that own and operate school buses and contract with school districts to provide pupil transportation service.

Safe Kids Worldwide

State and local Safe Kids Coalitions are active in all 50 states (plus the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico) with additional international efforts. Safe Kids provides information, programming and material educating adults and children to prevent the number one killer of children: unintentional injury.

Safe Routes to School (SRTS)

SRTS is an approach that promotes walking and bicycling to school through infrastructure improvements, enforcement, tools—including a guide and safety education—and incentives. SRTS programs can be implemented by departments of transportation, metropolitan planning organizations, local governments, school districts, schools, or even parents.